In May 1989 I traveled to Normandy , France. I drove there in the comfort of my rent-a-car, while enjoying the beautiful country side all around me. I arrived at Juno Beach and took in the breath taking view of the Atlantic Ocean, --- and no one was shooting at me.

In June 6, 1944 Jack Veness traveled to Normandy, France. He got there in an uncomfortable landing ship on the rough Atlantic Ocean, while his comrades got sea sick all around him. He arrived at Juno Beach wading through hip-high cold water, --- and everybody was shooting at him.

Recently, I sat down with Jack Veness and asked him about his time as a soldier, D-Day and the struggles that followed.

In May 1942, at the age of 19, Veness enlisted in the army, and headed off to Brockville, Ontario for officers training. There, he did the training to become a Second Lieutenant before going off to camp Utopia for advanced training to become a full Lieutenant.

And in May 1943, he and his fellow soldiers from the North Nova Scotia Highlanders -- known as the North Novas -- headed for England.

Veness and his regiment trained with British and United States forces, storming beaches in Scotland and southern England, training for the invasion of Normandy. At that time, they didn't know what they were training for, since it was such a well-kept secret even from the soldiers involved.

Veness and his comrades were given bogus maps in England of where they were going, he said, "When we were on the boats to going Normandy they passed out the real maps of the area, then we knew where we were going".

The first assault wave of soldiers landed at around 7:30 a.m. Veness and his regiment landed later in the morning at around 11:00 a.m. By this time the beach was mostly secure, but the shelling from the Germans was still going on.

"The next day was our tough day, the first day we only lost three or four men", Veness recalled.

During the first day his unit became the vanguard of the whole Canadian advance. It led the other units as they pushed inland. The Canadian's pushed almost 11 km that day - the longest stretch of all the units.

"There was very little resistance that first day. The second day was a little different, we lost about 75". Veness said, "That was 75 killed, casualties must have been in the hundreds".

On that second day, June the 7th, Veness and his vanguard unit made the deepest advance into France of any forces, including British or the United States.

"Then we were counter attacked, and when we were counter attacked the vanguard was too far ahead of the artillery, we had no artillery support at all".

On three occations, supporting troops tried to get to Veness's unit, but the German artillery kept them from advancing. Still, Veness managed to get 12 men to the next company about a mile back.

The Germans never let up and the Canadians were counter-attacked again several more times.

"They were pouring machine gun fire at us all that time ...I was terrified", Veness said.

He crawled through a trench next to a hedge that was so shallow, a man had to be on his belly to be below ground level.

" I was trying to get down below the lip of that trench every time this machine gun fire went by, it just swept up and down the hedge. We couldn't even see the Germans, they kept just sweeping it (the hedge) with machine gun fire, back and forth, back and forth, and every time I'd hear it coming I'd get down as low as I could."

The bullets were being fired over his head were so close, he could hear them going by.

"They make a snapping sound", he continued, "If you talk to anybody and he says the bullets were whistling by, they weren't there".

After about an hour and a half to two hours, the unit was finally surrounded and taken prisoner by the Germans. They then had a 220km walk to a prisoner-of-war camp in Rennes, France, which took them about 5 days. During this walk the Germans executed 18 men, which included seven from Veness's platoon. Later, as the men walked unarmed along the road, a German drove a truck into the line of men, killing two.

Once they reached the camp, Veness said the treatment wasn't too bad. The worse part, he said, was the food they received twice a day. It consisted mainly of rotten vegetables.

After spending about 5 weeks in the camp, Veness and some of his fellow prisoners were placed on a train to be taken to another POW camp in Germany. This was the break for which Veness and his comrades were waiting. He and 14 other prisoners kicked a hole in the end of the box car they were on and jumped off the moving train near Tours, France.

On the run in occupied France, Jack and his fellow soldiers hid in farmhouses, old churches and wherever they could find shelter.

Until one day while hiding in a cabin, they were discovered by members of the French resistance, called the Maquisards, also known as the Underground.

The former POWs spend about five weeks with the underground group, helping where they could, including showing them how to use some weapons.

During their time with the resistance, the Canadians found out about a possible route back to England.

"We had heard that there was a secret airport south of us somewhere, where planes came in and brought in supplies in for the underground". So Veness and fellow North Nova member Jack Fairweather and a Pilot from the United States made it to the airfield and on a plane back to England on August 26, 1944.

In late September, after being debriefed in England, the two Jacks linked up with their regiment, which was now in Nijmegan, Holland. For several months, they held ground in Holland, during which time Jack Veness was promoted to the rank of Major.

In February of 1945, they started a push down the Rhine and into Germany.

Veness was wounded one day near the end of March while in German territory.

"On March 30th I crossed the Rhine, and did a recognisance for an attack we were going to put in. While I was up in this tall building in a place called Emmerich, a shell hit the building and I was wounded, and that ended the war for me," he recounted.

After 12 days in a hospital in Belgium, Veness was sent back to England. When the war was over, he made it back to his North Nova regiment that were stationed in Holland. Of the 784 soldiers of his battalion that started on D-Day, fewer then 5 went home alive.

Veness will be among the veterans honoured for helping to fight for Canada's freedom on November 11, 2001 -- the same day he will also celebrate his 79th birthday.

Color photos, Graphics and Story by Stephen MacGillivray

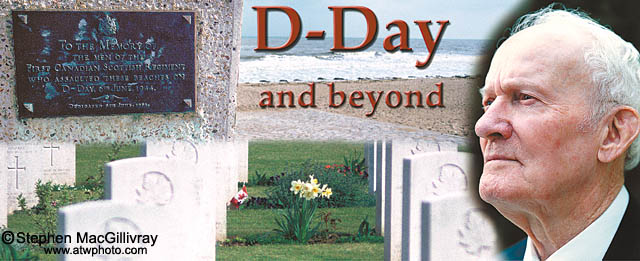

Photo Descriptions: The photos are starting from the top and going down: collage of photos including Juno Beach, Canadian War Cemetery at Beny-Sur-Mer, France and Veteran Jack Veness; Veness pins his Normandy and Prisoner of War medals on his legion jacket; Veness, second from right, with members of the French Underground; and Canadian War Cemetary at Beny-Sur-Mer, France where some of Veness comrades are buried.

| Home | Commercial | Aerial | Photojournalism | Portraiture | Grad-Photos | Contact |